A spotlight on food policy…and food policy research

Food policy is an umbrella term for all the policies related to the production, processing, distribution, purchase, consumption and disposal of a nation’s foodstuffs. The Common Agricultural Policy, the sugar tax, free school meals and food labels are all examples of food policy. The Covid-19 crisis presents food policy challenges - from directly providing food to the vulnerable to ensuring there are enough agricultural workers to pick crops - not seen to such a degree since the Second World War.

It also illuminates how many parts of government are involved in food-related policy, covering the food supply chain, food insecurity, nutrition and safety, livelihoods in the food sector, food in schools, delivery, and more. This fragmentation – an arrangement which has been criticised at the best of times – looks increasingly inadequate in periods of food system crisis. The pandemic created an intensified requirement for policy coordination, and exposed ‘governance gaps’ where food policy remits need clarification - for example, ‘hunger’ falling between the cracks of current departmental responsibilities.

Such shocks highlight the importance of food policy having a solid evidence base on who is responsible for what, and the connections between their activities, to support a quick and connected policy response.

Triangulating how food policy is made

The evidence base on the development of food policies in many countries is poor: the primary focus is on analysis and evaluation of

policies themselves not

how food policy is made. The

process of policymaking can be opaque and hard to research. A popular political science metaphor is the

‘black box of policymaking’ - much happens behind closed doors, and can be politically-sensitive.

Building evidence about policy making relies on triangulation of multiple data sources, including interviews, policy documents, media coverage, and reports and academic literature. Triangulating, or combining and comparing, data sources to understand the development and implementation of policy can be applied to many topics (see for example

Payne-Gifford on UKRI research policy or

Sharman on energy policy). It has been used to interrogate the development of specific food-related policies, but is less commonly applied to how food policy is made across a

whole government. Addressing this gap has been the focus of my work during the past couple of years.

This includes a project called

Rethinking Food Governance, for the

Food Research Collaboration, about how the government makes food policy in England. The documentary sources for the research were wide-ranging - partly because the way government activities in England are communicated. The design of the public-facing Gov.uk website, means there is no one place a researcher can go to identify – for example – the food-related responsibilities and policies of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Departmental websites do not offer an overview of the entire policy portfolio or current status of policies, and annual reports may only focus on headline activities. Details on which departments are working together on a particular issue are rarely provided. As a result of this, documentary sources included:

- departmental websites;

- annual reports;

- strategic plans;

- press releases;

- Parliamentary Select Committee reports and evidence submissions;

- National Audit Office reports;

- consultation responses on departments activities;

- reports from external organisations;

- media coverage.

This data was supplemented with 23 anonymous qualitative interviews with stakeholders from within and outside government. The interviewees confirmed and supplemented documentary findings, and offered perspectives on how current arrangements were working.

How to map who does what

The first output of the project was a report presenting each department in English government according to a template covering its:

- policy responsibilities and goals;

- key food-related laws/policies/strategies;

- size and structure;

- agencies (such as non-governmental bodies);

- advisory board;

- stated links to other departments, local government;

- the other UK governments in the devolved regions;

- and any stated examples of cross-government working.

Departments with a significant role in the food system are featured in more detail, and peripheral departments less.

A visual tool summarising who does what was created, providing a ‘map’ of the food policy system (see Image 1 below), refined with the help of a graphic designer (and then checked with policymaking contacts in government). The aim is to assist those working inside and outside government to understand at-a-glance the food policy landscape, from a holistic perspective. It identifies who holds potential levers for change, which may not always be in departments traditionally associated with ‘food policy’. Those campaigning for change, for example, can see which department/s they may need to contact to deliver their ideas, or where departments can be suggested to work more closely together.

Image 1: All government departments with responsibilities relevant to food

Visualising food policy connections

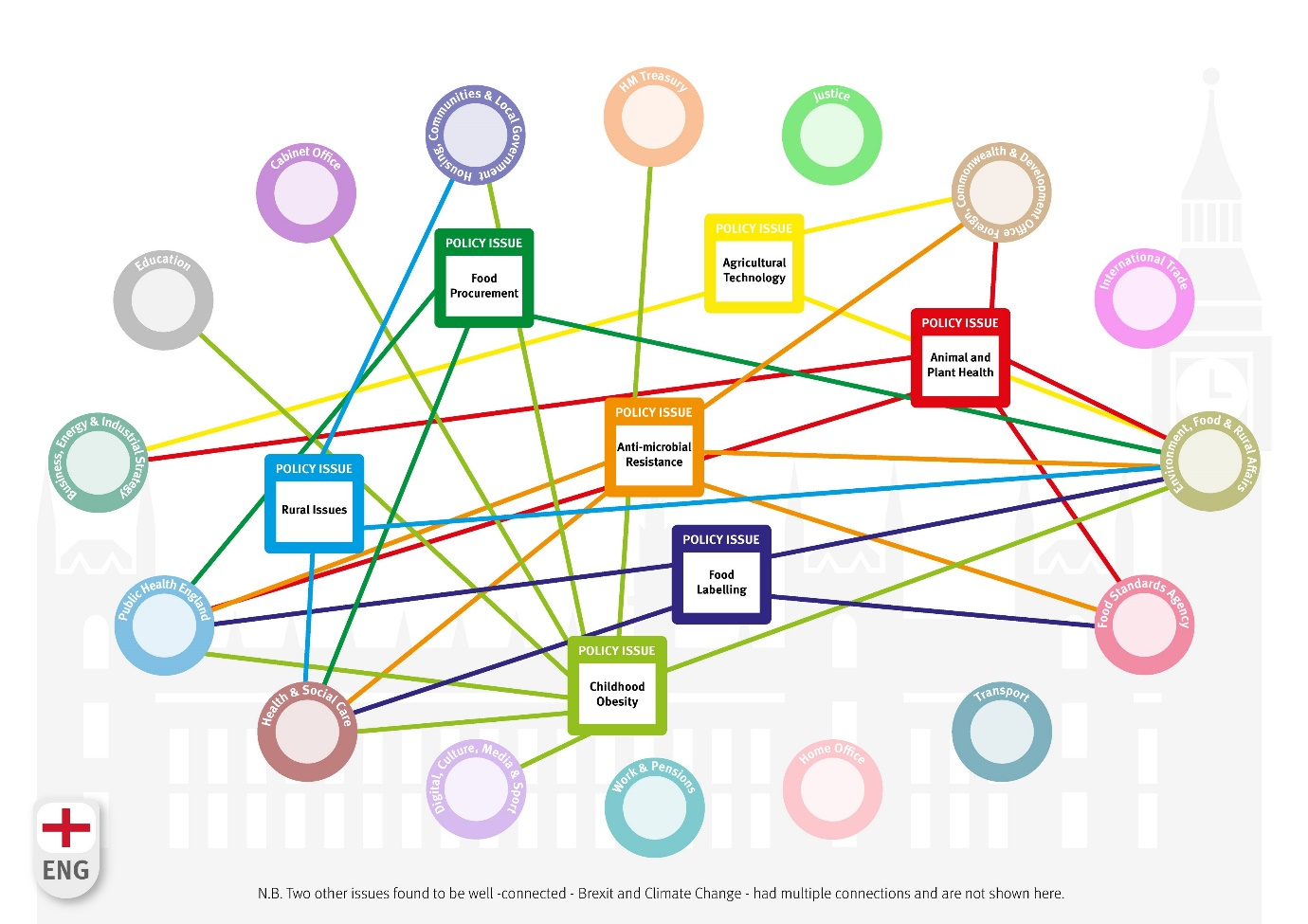

The next phase of the research involved developing a bottom-up ‘screening’ process, using policy documents and interviews, to identify where connected working on particular issues was happening, and where policy was perceived to be disconnected. The resulting report on who works with who - ‘Mapping cross-government work on food system issues’ – details nine examples of connected working, and 14 disconnections, with accompanying visuals based on the original map of departments.

,

,

Image 2: Selected food-related issues (in boxes) with good connections across different departments (represented by circles) in England’s national food policy

Challenges of food policy research

One of the main challenges for the mapping research is that data was collected in 2019, providing a snapshot of that time. The fast-changing policy and political environment means there have been changes to departments: EuExit closed, the Department for International Development merged into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Nevertheless, the mapping provides a baseline which can be applied and updated - for example, for an analysis of the food policy response to Covid-19. It also provides a method for other countries to follow. Similar exercises have now been completed on who makes food policy in India and in South Africa.

Perceptions of dis/connection are rooted in visions for the food system, including whether it should prioritise health, environmental, economic or social objectives. Interviewees working inside government (as civil servants or other officials) tended to think that food policy was already fairly well connected, while interviewees working on food policy outside government (in business, civil society, or academia) tended to think it was not. The search for policy connectedness and coherence is not merely a technical exercise in adjusting policies. This has important implications for policymakers looking to explore connections in future, including the need to build consensus through an inclusive approach.

Image 3: Selected food-related issues (in boxes) with scope for better connections (represented by the broken links) across different departments (represented by circles) in England’s national food policy

New governance arrangements for food policy?

Food crises inevitably raise questions about whether a new arrangement or ‘mechanism’ to connect policy is required, and Covid-19 is no different. Again, the evidence base on the kinds of governance mechanisms available to connect food policy, and effectiveness of these, is poor. This makes exploring new ways of governing, including through policy learning between countries, more challenging.

Part of my work has been to identify how connected working is supported in England and in other countries. Which food governance mechanisms, such as personal connections, issue-specific taskforces or dedicated food committees, strategies or bodies, are used? This may help us to take advantage of the opportunity, presented by food’s rise up the agenda, to redesign governance arrangements. My hope is that researchers in other countries are encouraged to put their own food governance arrangements under the microscope, augmenting the evidence base for the benefit of all.

Bio:

Kelly Parsons is a postdoctoral researcher on policy and governance related to food systems. Her research covers: food policy – past and present; policy integration; policy coherence; food governance arrangements; and systems approaches to food. She is a Research Fellow in the University of Hertfordshire Food Systems and Policy Research Group. She has a Masters in Food and Nutrition Policy, and a PhD from the Centre for Food Policy, City, University of London.