Earlier this year, Healthwatch England conducted a poll with 2,000 people about their attitudes towards the Covid-19 vaccine, which identified differences in attitudes between different ethnic groups, with some expressing greater hesitancy towards the vaccine.

We were commissioned to partner with Healthwatch England and the NHS Race and Health Observatory to dig deeper into the reasons behind the lower confidence in the Covid-19 vaccine roll-out programme among some ethnic minority people living in England – aiming to provide critical lessons for current and future public health campaign and to help tackle health inequities.

Our methodology and approach

Recruited through a specialist market research recruitment agency working with ethnic minority groups, the Healthwatch England network, and targeted social media activity, 95 participants from African, Bangladeshi, Caribbean, and Pakistani backgrounds took part in the research. Each had primarily hesitant attitudes or lacked confidence in the vaccine.

With a subject matter as charged and controversial as Covid-19 vaccination uptake, it was fundamental that participants felt they could confidently share their views and feelings openly with one another, without fear of judgement.

With narratives and insights about the vaccine constantly emerging, it was also essential that the research was designed to be responsive to capturing developing stories and information sources.

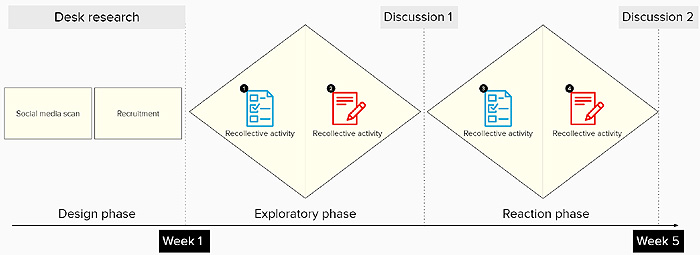

In line with Covid-19 lockdown measures, we opted to use an online research and engagement platform to create a series of activities undertaken over a period of five weeks, completed by 95 participants. Participants used a personalised online profile to respond to questions, engage in facilitated discussions and share real media examples of information about the Covid-19 vaccine from sources they trusted.

The use of the online platform meant we could gather and share insights as they emerged, as well as iterate the design of the research to factor in news stories as they developed. For example, participants could comment on how reports of the AstraZeneca vaccine being linked to blood clots, or messaging from public health officials, influenced their attitudes and beliefs.

Thirty-five of the participants joined two facilitated online workshops hosted in the second and fourth weeks of the project to further explore and test themes emerging from the online activities.

Figure 1: The research process

A further six telephone depth-interviews were also held to provide people who are digitally excluded, or for who English is a second language, to share their insights.

Read the research findings in the VacciNation report

Our approach resulted in important insights into public health messaging around vaccination. Participants trusted institutions that were seen to be acting independently of government (e.g. the NHS, scientists) and were receptive to messages from frontline healthcare workers, doctors and everyday people (as opposed to celebrity endorsements). Targeted messaging could miss the mark and make people feel singled out (local and direct engagement was felt to be more effective). Transparency increased trust. Individual agency in making decisions about vaccination was important.

Creating a safe space - what we learned

Giving people time

We staged this research over five weeks because it created the space for participants to really reflect on their position when it comes to the vaccine. This led to longer format and more detailed responses, allowing for nuance to exist. This is reflected in the fact that hesitancy towards the vaccine is on a continuum and rarely fixed.

Building trust between participants

All data from the online activities was private which made participants feel comfortable about sharing their genuine opinions. When it came to the group discussions, facilitators created the space at the beginning of the workshop for participants to share how they felt about the vaccine, cultivating an atmosphere of openness and trust.

Building trust with facilitators

It was important to be explicitly clear to facilitators that while they should draw from their personal experiences where relevant, their objective was to create a non-judgemental space for participants to share their views.

We also made sure participants understood that Traverse and Healthwatch England are independent from the NHS/Government. As our colleague Jacob Lant, Head of Policy and Research at Healthwatch England said about the research, “It was not about trying to convince people to take the vaccine, but about understanding their questions and using that insight to help Government and the NHS adjust the roll-out so people feel confident in making the decision that is right for them.”

The benefits of an online space vs. face-to-face

The online workshops were held on video calls due to lockdown, which is the next best thing compared to face-to-face workshops. While it can make it harder to facilitate a natural discussion, video calls were more practical when engaging participants from across England simultaneously.

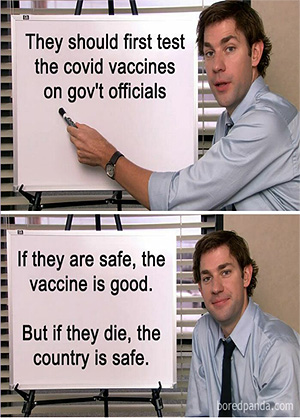

Using an online platform meant participants could submit responses to the activities using a multimedia format. This allowed for the research team to design activities that asked participants to upload examples of news items or messaging they had received about the vaccine, as well as respond to questions using video or audio recordings.

Figure 2: A meme submitted by one of the participants: "It is kind of true because they are the ones to approve them but we need to feel safe about it"

The platform also meant that the project team could design activities asking participants to comment on videos and images used in the media about the vaccine. An example of this is our use of a video of Black and Asian celebrities and sports personalities encouraging people to take the vaccine, which we were able to share and then invite feedback.

‘It very much reflects the white gaze (throw a bunch of 'BAME' people together as though they are not from separate and heterogenous communities), appeal to racial stereotypes (e.g. Indian doctors), push the desired narrative with a script of 'facts' and 'debunking' rather than encouraging genuine dialogue, etc. It felt like the way the NHS tries to appeal to us, there is no effort to actually understand and address the reasons for our reluctance / refusal and thus came across as patronizing / inauthentic...speaking at us rather than to us.’

[Response to a Guardian vaccination media campaign featuring celebrities]

Empowerment

One of the key findings from the project was that participants expressed gratitude that they were finally being asked to share their opinions on the vaccine instead of assumptions and generalisations being made based on their ethnicity.

Inclusivity

The recruitment strategy of going through three different routes – market recruiter, community groups and via the Healthwatch Network - aimed to ensure that this project was an opportunity for people who don’t usually take part in research projects to have their voice heard. The in-depth interviews were put in place for people who may be digitally excluded or for whom English is a barrier.

What’s next?

Tackling health inequalities requires us to build trust. Increasing levels of trust with certain communities will require empowering members of that community to voice their concerns and opinions. Community engagement activities are key to supporting this and we are seeking opportunities to discuss the findings of this research with anyone interested in developing their engagement activities.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank all the participants who gave up their time and trusted our process. I also want to thank my amazing team of facilitators and designers: Ella, Maddie, Naomi, Noel and Shazia, and the Healthwatch England team.

Author Bio

Louis Horsley is a consultant at Traverse specialising in research and evaluation in the health and social care sector.