Citizen science is an ‘umbrella’ term that describes a variety of ways in which the public participate in science. The main characteristics, as defined by the European Citizen Science Association, are that:

(1) citizens are actively involved in research, in partnership or collaboration with scientists or professionals; and

(2) there is a genuine outcome, such as new scientific knowledge, conservation action or policy change.

While more common in the natural sciences, particularly disciplines focusing on the environment and climate change, it is increasingly crossing the theoretical divide and being used within the social sciences.

Citizen science is a method with historic roots

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were the era of the amateur scientist. Men and women such as

Charles Darwin,

Mary Anning, and

Caroline Herschel made significant contributions to science despite often not having formal scientific qualifications. Many were founding figures in their respective fields. However, the amateur scientists of the eighteenth and nineteenth faced many barriers having their findings accepted by the establishment of the time, especially if they were women.

The twentieth century saw the natural and social sciences become increasingly formalised and, some may argue, removed from the public realm. Degree-level study has become a pre-requisite for entry into many science professions. Academic credentials are often required for findings to be taken seriously.

Although efforts are increasingly being made to widen access to social science through modern apprenticeships and initiatives such as

MRS’s apprenticeship programme, and work by the

Government Social Research profession to provide work placements and summer schools, there is a perception that science is closed off from ordinary people.

Or is it?

Citizen science is an increasingly popular method for bringing the public and the scientific establishment together.

The term ‘citizen science’ was coined independently by academics in the UK and the US in the 1990s. But, these UK and US based academics used the term in subtly different ways.

In his 1995 book, Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development, Alan Irwin considers that science is an inherently human activity rather than “an alien force”. He argues for a re-evaluation of the relationship between science, technology and citizens, and for the public and those with academic expertise to be brought closer together. That same year Rick Bonney used the term in a more purposive way to describe the increasing use of the public in the collection of ornithological data. At the time the Cornell Lab of Ornithology was using volunteers to collect longitudinal information about birds’ habitats and locations.

These conceptualisations of citizen science as principle-led and pragmatic underscore the breadth of applications the term is still put to.

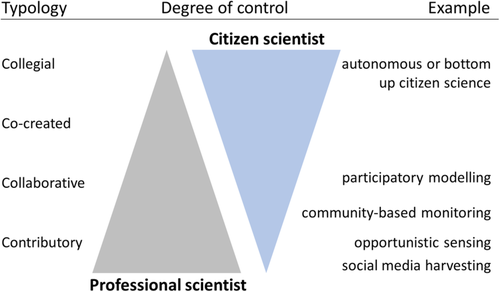

As with other forms of citizen engagement and participation, there are various typologies of citizen science which can be distinguished by the degree of control the citizen scientist holds over the project compared with their academic partners and the nature of their relationship (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The relative degree of control of citizens and professional scientists for different typologies of citizen science. Reproduced from David Walker, Magdalena Smigaj and Masakazu Tani’s 2020 article “The benefits and negative impacts of citizen science applications to water as experienced by participants and communities”

Projects labelled as citizen science can involve citizens in drastically different ways and at different points in the research cycle. Some ask citizens to support with discrete aspects of the research process, for instance, with the collection of data or with data analysis. Projects such as Patientslikeme ask members of the public with chronic health conditions to upload their health data for further research; the World Wildlife Fund’s “Walrus from Space” project, delivered in partnership with the British Antarctic Survey, asks members of the public to spend time searching for walruses in satellite images taken from space to support analysis.

Other projects engage citizens throughout the scientific process and involve citizens in the choice of topic to be researched, the research design, data collection and analysis and reporting. For example, f

ellow SRA blogger Sophie Payne-Gifford and her co-writer Gemma Hamilton described their involvement in a Wellcome Trust funded citizen science initiative, the

Parenting Science Gang. The pair were volunteer participants in a

project which brought together healthcare practitioners and those with personal experiences of breastfeeding to understand the effect of healthcare practitioners' own experiences on their professional practice.

Whatever form citizen science takes it has the potential to provide a range of benefits.

These benefits can be realised by the individual citizen scientist involved in projects, the scientist and institutions involved in supporting them and the wider field or issue being researched.

- A meaningful contribution to knowledge: whether collecting data, analysing images, or shaping the research design from end to end, citizen science projects can generate new knowledge that provides immediate benefits to the project team and the wider community.

- A richer, deeper understanding of the issue: involving citizens means data can be gathered that may not otherwise be accessible to academics due to either funding or resource constraints or lack of access to people with the lived experience of an issue. Large volumes of data can also be collected and analysed giving more power to research projects.

- Greater public engagement, awareness and education: citizen science projects can attract media attention, highlighting issues surrounding the subject of the citizen science project; those directly involved gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter and the scientific process.

- Strengthening of relationships between citizen scientists and scientific institutions: participation can also build trust and confidence between scientists, institutions and the public as both parties can build understanding and respect for each other’s work, experience and perspectives.

- Empowerment: Connected to the above, gaining skills, understanding and access to institutions can empower citizen scientists to act on the issues which are important to them. This can increase participants’ social capability and see local, traditional and indigenous knowledge and priorities foregrounded and given increased status.

- Change: having a deeper understanding of an issue can support individual behaviour change and the inclusion of insights from citizen science projects in policy change, leading to wider benefits which extend beyond individual citizen science projects.

The FSA and UKRI are supporting the use of citizen science approaches with 6 pilot studies running across 2022.

The FSA places science and evidence at the heart of its activities. It employs dedicated teams of social scientists, analysts, economists and natural scientists to ensure its policies, decisions and advice are based on the best available evidence.

In late 2020, the opportunity came along to collaborate with UKRI on supporting the use of citizen science methods. In March 2021, the FSA and UKRI, with the support of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), launched the Citizen Science for Food Standards Challenge. The challenge included a fund worth £200,000 and had the purpose of funding citizen science projects investigating the FSA’s areas of research interest.

In September, an independent panel of citizen science experts and leading academics selected six projects to receive funding. These projects tackle diverse issues ranging from an exploration of the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), to engagement with consumers with food hypersensitivities, to understand experiences ordering food online. Through funding these projects the FSA and UKRI hope to understand the potential for using citizen science to inform public policy, within the social as well as natural sciences.

Sharing what we learn – all eyes on Winter 2022.

It is too early to say what we will learn from these citizen science projects. Most started their work in January/February 2022. If 2021 is anything to go by, we can expect to encounter a number of challenges along the way if only from the ever-changing context of Covid.

What I can say is that what we learn about the process of running a funding call on citizen science, and from engaging with the academics running these projects, will be shared here. By the end of 2022 we should have a clear sense of what makes a good citizen science project and be in a position to share some tips and tricks for setting them up, engaging citizen scientists, devising protocols, analysing data and sharing results.

Ahead of this, the FSA are scoping a ‘Citizen Science for Policy’ event, in partnership with UKRI and the Government Social Research (GSR) innovative methods community. Citizen science experts will outline the main principles and benefits of the method and how to increase policy engagement. The event will aim to raise awareness and build capacity across the research community and will provide useful networking opportunities for anyone with an interest in citizen science. If you would like to be kept informed about this event or have an example of citizen science you’d like to share, please contact me at:

[email protected].

Author Bios:

Anna Cordes is a Senior Social Science Research Officer at the Food Standards Agency (FSA). Before joining the FSA, Anna worked at Which?, the Consumers’ Association, as a Senior Policy Researcher and at Kantar Public. She has recently completed an MSc in Social Research at Birkbeck, University of London.