Groups who were at risk of poverty before the pandemic, such as those living with disability, are thought to have become more at risk during the pandemic, entrenching existing inequalities. There are increased costs associated with digital exclusion and access to groceries, increased care needs due to the closure of services and increased caring responsibilities (meaning many carers have had to cut their hours of work or have lost their jobs).

JRF argues that the UK needs a stronger social security system that as a minimum protects from destitution, but which should also help people find a route out of poverty, and which should be designed with the people who rely on it at the heart of the design.

The lived experience of health inequalities

As well as being a risk factor for poverty, poor health and disability are a consequence of living in poverty. Those living in poverty are more likely to visit A&E, have lower life expectancy and experience emotional distress and poor mental health. This was brought to life by Suzy Solley from Groundswell, a London based charity who work with people who have experienced homelessness.

Groundswell involves people who have experienced homelessness in all aspects of their work: homeless health peer advocacy, insight and action (with volunteer peer researchers), and in progression projects that support staff and volunteer wellbeing.

Due to a lack of research in this area, a recent project has looked into the connection between women, homelessness and health. Women’s experiences and pathways into homelessness are often different to men’s and may be associated with specific health inequalities.

The four peer researchers in the project were women who had experienced homelessness and who were able to interview other similar women (77 interviews, 3 focus groups with 104 women), take part in interview coding workshops, or reflect on the quotes and transcripts of interviews in a series of reflective podcasts about the findings recorded by a specialist facilitator.

Groundswell felt that the understanding, empathy and love of the peer researchers for the research participants was key to the success of the project. The process of doing the research was as important for those involved as the findings of the research were.

Women talked about the multiple and interconnected reasons that had led to homelessness (often combinations of relationship breakdowns with poor physical and/or mental health). The women described how homelessness then made existing health conditions worse and gave rise to new conditions.

Conditions associated with poor sleeping conditions were common, such as joint, bone, heart and foot problems. Erratic eating patterns and difficulties maintaining hygiene (e.g. access to showers and sanitary products) also increased the risk of poor health. There was a strong connection between the stress of homelessness and physical health (e.g. headaches, hair loss, stopped periods and, more severely, self-harm and suicide). For women with children, poor housing and the poor health of a child could impact on the health of the mother, or there could be issues and distress around a child being taken into care.

The women found that daily life was full of competing priorities (e.g. keeping clean becoming difficult to maintain). Many found themselves in Catch-22 situations, unable to access services due to a lack of a permanent address or being perceived to have bigger mental health or substance misuse problems that were prioritised over more minor, but still significant, health concerns. Importantly, 65% of the women in the study reported that they struggled to find the confidence and motivation to access healthcare.

Talking to the public about health inequalities

One approach to tackling such complex health inequalities is to direct resources to those who need them most. Becky Barwick talked about the NHS Leeds Clinical Commissioning Group [CCG] targeted approach to tackling health inequalities with Georgina Culliford (Qa Research), who led a series of online workshops in summer 2020 to explore the attitudes of the Leeds population to the CCG’s plans.

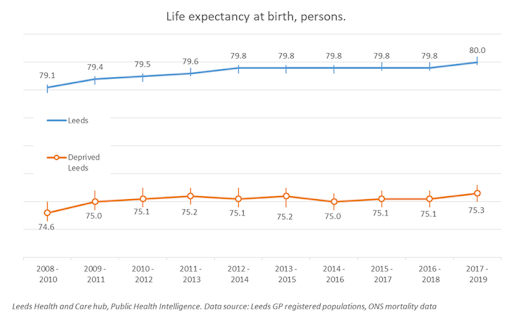

Health intelligence shows that 20% of the population of Leeds live in areas that are classed in the 10% most deprived in the country (Multiple Indices of Deprivation). In these areas, ethnic minorities are overrepresented and life expectancy is nine years shorter than in the rest of Leeds. The life expectancy gap was already widening before the pandemic, and is likely to be wider following the pandemic.

Leeds CCG are applying the principle of ‘proportionate universalism’. In ‘Fair Society, Healthy Lives’ Michael Marmot proposed that in order to reduce health inequalities, health services should be resourced proportionate to level of need. This is a principle of ‘equity’ of health outcomes, rather than ‘equality’ of access to health services.

Leeds CCG will operationalise their equitable approach through 19 Local Care Partnerships who are empowered to target neighbourhood services according to local need. Areas with greater deprivation will receive greater GP funding per head than other areas. In addition, the CCG will support Community Development for public health.

However, equality of access to the NHS is highly valued by the public, and so the CCG had commissioned QA Research to conduct a deliberative event with Leeds citizens in April 2020 to gauge attitudes to the introduction of targeted investment in health services. Due to the pandemic this became a series of group zoom workshops, plus one-to-one depth interviews for those less confident online (55 participants overall, representing the variation of the Leeds population).

The first step was to ‘bake in’ an understanding of the concepts of equity and health inequalities. Participants found the nine year difference in life expectancy between Leeds postcodes particularly shocking. Of course, this consultation took place at the height of the pandemic, when there was a great deal of discourse in the media about health inequalities. Participants were well versed in some causes of health inequalities, such as poor and overcrowded housing. Less well understood were indicators of health inequalities such as illness free years or ‘access’ to healthcare in a broader sense (rather than just travel and transport).

Overall, participants were supportive of the CCG’s plans for targeted investment, once the principle of equity was understood. They appreciated seeing lots of detail about the background to health inequalities and to support the plans. However, there was a need for reassurance that access to emergency and vital services would not be impacted, and some opposition relating to the perceived relationship between lifestyle choices and health inequalities.

Case studies were seen to be a good way of communicating the plans and bringing them to life, and this will inform key messaging from the CCG, who plan to highlight compassion, personal stories and examples.

Future priorities for research

Reliable data about the

impact of the pandemic on health and society is only just becoming available, and it may be a matter of years before the impact is fully mapped and understood. The speakers pointed to areas of future work, such as better understanding the intersection of age, gender and disability and differential effects of the pandemic. The public’s interest in and attitudes to health may also have changed, and it will be interesting to see if the greater awareness of inequalities amongst the public is influential in the future. A final message from the speakers was that decision makers also now have more awareness of health inequalities and want to act quickly, but while there is a need to minimise harm during the pandemic, these issues are complex and require long term solutions.

Meet the speakers:

Georgina Culliford is a Research Executive at Qa Research (a social research agency based in York), and convened this seminar as part of her role as committee member of SRA North Georgina worked with

Becky Barwick (Head of Strategic Development, NHS Leeds CCG) on the public’s response to NHS Leeds CCG’s new strategy to tackle health inequalities.

David Leese is Analysis Manager at The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, an independent social change organisation working to solve UK poverty. David previously worked at NHS Digital.

Suzy Solley is a Research Manager at Groundswell. Groundswell works with people with experience of homelessness, offering opportunities to contribute to society and create solutions to homelessness. They believe people who have experienced and moved out of homelessness should inform the solution. They have a national network of volunteer advocates and researchers who have experience of homelessness.

Find out more:

Watch a recording of the event on youtube.

See the slides on the SRA website.

Follow SRA North on twitter.

This post was adapted from meeting notes and slides by Dr Cath Dillon (SRA Blog editor, and SRA North Committee member).