The relationship between researchers and refugees

As researchers, we need to be aware of potential power imbalances that may be at play when we conduct research with refugee communities. These can come about as a result of, among other things, refugees’ uncertain legal status; insecure economic position; the impact of trauma and health inequalities; and/ or minority ethnic status in the country in which they are living. This imbalance can leave participants feeling vulnerable and potentially under pressure to take part or to represent their experiences in a certain way.

We need to consider how we can rebalance the relationship and provide reassurances to participants at each stage of a project - for example, when talking about the research and explaining their rights; designing the research to elevate refugee voices; and considering how findings are reported and shared.

Be clear about your intentions

While all research requires careful consideration around ethics, there are some specific things that can help ensure refugees can give their active consent to take part. For example, the languages spoken, backgrounds and education levels of refugees are diverse – some may have university degrees, while others may be unable to read or write.

We have found that ‘gatekeepers’ - individuals who can act as an intermediary for the researcher to invite refugees to take part - can play a critical role in supporting the researcher to reach out to people and explain the research. However, identifying appropriate gatekeepers – whether a caseworker, charity or volunteer group – also requires careful thought. They should be trusted, but also neutral as far as possible in relation to the research. It is important that they do not exert influence over who takes part, as this could reduce the diversity of views represented in the research.

Researchers and gatekeepers must also communicate the voluntary nature of the research and that people will not be negatively impacted in any way should they decline or change their mind about taking part. This is particularly important when organisations or bodies involved in providing direct or indirect support to refugees are involved with the research.

Many refugees will also have ongoing fears for their, or their family members’, safety. Therefore, how any personal data will be collected, used and stored carries particular significance. Given this, it is vital to consider carefully what personally identifiable data it is strictly necessary to collect; uphold robust data security processes; minimise data transfer; and anonymise/ pseudonymise data sets as far as possible. Asking participants to choose a pseudonym can emphasise that their identity will remain confidential. Making it clear that participants will not be identified in any research outputs – and how this will be done – can also provide important reassurance to participants.

Promoting Inclusive research techniques

Whether in the country they have fled from, or while living in a host country, many refugees will have experience of not feeling valued or listened to. Qualitative research provides an opportunity for the refugee participant’s voice to come to the fore, which can be a powerful and meaningful experience. This is just as relevant for the data collection stage as it is for reporting. For example, it can allow research encounters to focus on what is most important to participants, as well allow for the use of quotations and case illustrations when writing up findings.

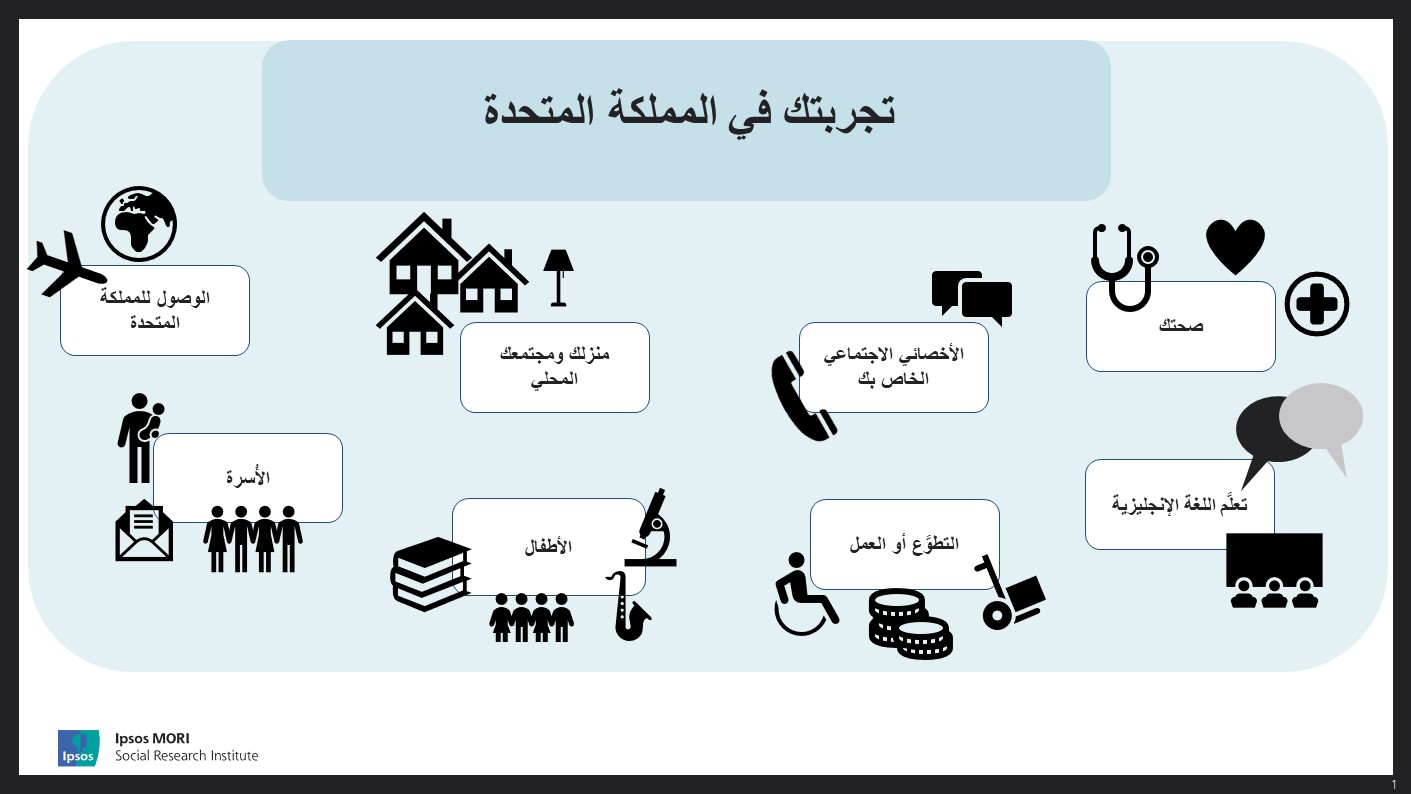

There are a number of ways we as researchers can give participants greater control over the direction of the research, to allow their voice to come through. For example, using broad questions to start the discussion can allow participants to focus the conversation on the issues that are most important to them, or that they are most comfortable discussing. The interviewer can also guide the conversation with probing questions and visual aids (see figure 1 below), which can help participants recount their experiences in a level of detail they are comfortable with. This is often helpful when discussing potentially distressing or difficult subjects. Consider providing participants with translated information leaflets with relevant local or national trauma services. Giving these to all participants before the research encounter starts and explaining that this is standard practice for all participants in the study means people are less likely to feel singled out.

Figure 1: Visual aid used in qualitative research with refugees in the UK to show participants the structure of the research encounter

As well as providing insights into how participants’ lives change, longitudinal approaches – returning to speak to the same person or family over time – can help researchers to build rapport and trust. This can lead to more open discussions. For example, we have found that it is often easier to broach more sensitive topics – such as mental health or experiences of hate crime – during a follow-up visit, when these topics may also emerge spontaneously. Where possible, keeping the interviewer and interpreter the same can also promote greater consistency and continuity in the relationship.

Think about who is doing the research

Refugees have diverse identities and often complex histories, making it important to consider who undertakes the research. For example, gender-matching researchers and participants can open up topics that people may not be comfortable discussing with someone of a different gender.

Refugees may also feel uncomfortable speaking openly about their experiences with people from the same nationality or ethnic group. This is particularly the case for refugees who identify with a minority ethnic group, or who have experienced persecution (for example based on their sexuality, gender identity or political opinion). When conducting research with refugees in the UK, we noted that some participants felt uncomfortable speaking through interpreters who spoke with certain accents, due to fears that the interpreter might share what was discussed within their community and potentially put family members living abroad at risk.

Communicating across cultures

Including refugees in a quality assurance or advisory role on the project can provide invaluable feedback on the approach and advice about what to consider when researching specific communities – such as how questions should be posed, or findings framed and shared.

Interpreters in qualitative research can also act as a cultural bridge between the researcher and the participant. For example, interpreters can advise on appropriate behaviour and help ensure researchers do not commit any inadvertent faux pas (further building on the role of gatekeepers and refugee expert advisors). For example, the interpreters supporting our research in homes with Syrian refugee families provided useful insight on details such as what socks to wear: nice ones, with no holes, as we would likely be expected to remove our shoes. Interpreters also helped researchers politely decline (or accept!) offers of food and drink from participants displaying the Middle East’s famous hospitality.

You can read more about working with interpreters to conduct qualitative fieldwork online and by telephone in this blog.

Sharing research findings with refugees

Refugee involvement in the research should not necessarily stop when the research encounter is over. Having given their time and energy to help with the research, it is only right that participants and others involved can see the result.

Consider how findings can be shared with individuals and communities, and in what format. A visually engaging format that uses images may be more accessible than a lengthy written report. For a recent project, we plan to share findings with participants in a short visual and written output translated into relevant languages.

We cannot walk alone

We invite other researchers to leave a comment and share their own reflections and experiences about conducting research with refugees and ideas about how to increase understanding about refugee issues, while promoting refugee voices.

Author Bios

Ipsos MORI conducts wide-ranging research with refugee audiences. Alongside evaluations of public policy related to refugees and asylum seekers, Ipsos MORI undertakes polling on public attitudes, international research with refugee audiences, and wider research looking at ethnic minority experiences, discrimination, hate crime, cohesion and integration. Ipsos MORI has also partnered with Breaking Barriers to support employment opportunities and help overcome barriers to employment for people from a refugee background, as well as to amplify and celebrate the valuable contribution made by refugees, both in our business and to society.

Charlotte Peel is a Research Manager and migration policy expert in the Cohesion and Security team. She works mainly on projects related to migrants, asylum seekers and refugees in the UK – including government policy evaluations and research on public perceptions. Contact Charlotte if you’re interested in finding out more about our UK refugee and migration research.

Andrew McKeown is a Research Manager in the Qualitative Research and Engagement Centre. He specialises in qualitative methods and works on evaluations and qualitative projects about a range of topics. Get in touch with Andrew to discuss relevant methods for research with refugee audiences.

Ilya Cereso is as a Consultant in Ipsos MORI’s Sustainable Development team. She has worked on domestic and international evaluations of programmes supporting refugees. She is also a volunteer employability mentor for Refugee Action. Get in touch with Ilya if you have a question about our international or development work.

Lauren Porter is a Research Manager who works across Ipsos MORI’s Politics and Society and Cohesion and Security teams. She specialises in conducting qualitative research with harder to reach audiences and on sensitive topics, across a range of policy areas. Lauren is also a volunteer research for the social initiative Give Your Best. Contact Lauren if you would like to hear more about this initiative, or about conducting research on sensitive topics.