What is the Student Kitchens project?

Many of us look back on our student days and remember the washing up piled in the sink for days, the mouldering anonymous vegetable (or, more likely, leftover takeaway) in the back of the fridge and think of the general lack of food hygiene with a small shudder. Such mess can be a breeding ground for pathogens and make the risk of food borne disease greater.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA), in partnership with Food Standards Scotland (FSS), wanted to understand more about the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of university students in relation to food safety, food security and hygiene practices. A key aim was to gather evidence in this space (is student food hygiene really as gross as we all remember?) and identify unique challenges and experiences of living in halls of residence and shared accommodation. It is important for the FSA to understand the behaviours of students to assess the risks facing them and provide an evidence base for policy, such as student-specific communications to increase food safety knowledge and behaviours.

We thought about several ways we could go about meeting our research objectives and how we could use this project to build connections with an under-researched and somewhat hard to reach group – students. We settled on a co-designed approach with students, employing citizen science principles and digital methods to ensure we could gain a rich understanding of this audience:

- Phase 1: Co-creation sessions: to understand the challenges and experiences of students to inform and develop the online survey, adapting existing questions from Food and You 2 (F&Y2), the FSA’s flagship survey and source of official statistics, where possible. This allowed us to use cognitively tested questions (increasing the validity of responses) and support comparability between the data sources.

- Phase 2: Online survey: to gain quantifiable data on the student population which can be used to influence policy and student-specific guidance for those in shared accommodation. The F&Y2 sample captures households, so communal living establishments such as halls of residence is an evidence gap that the student survey aimed to fill!

- Phase 3: Zooniverse: to use the power of the crowd by partnering with citizen scientists to code thousands of images of students’ kitchens and sinks and deliver statistics about the reality of hygiene and food safety adherence of UK students.

In the case study below, we describe each of the project stages in more detail and provide top tips and lessons learned (the takeaways, if you will) along the way. Our interim findings report, published in January 2023, contains the findings of the co-creation sessions and online survey.

Co-creating research materials brought unknown, topical issues to the surface, but presented ethical challenges

Sixteen university students took part in 4 co-creation sessions between July and December 2021 to inform the development of an online survey. Each co-creation session lasted up to two hours and participants received a £20 voucher as a thank you for their time.

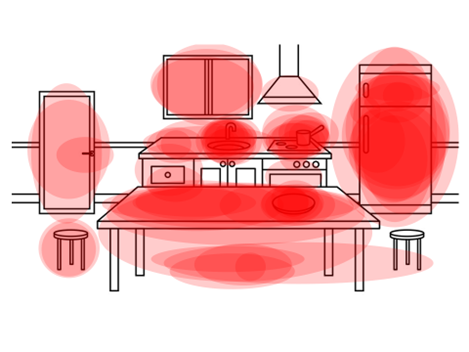

The first three co-creation sessions focused on the identification of experiences and challenges relating to food safety, food security and diet. The sessions consisted of a brief introduction to the topics and a group discussion on key experiences and challenges in shared kitchens. As part of the session, students took part in a visualisation activity where students identified food safety ‘hotspots’ in the kitchen. The heat map creatively indicates the key areas that students need further food safety guidance on and points towards a gap in research that went on to shape the subsequent stages of research.

Heat map of the food safety hotspots identified by students

The co-creation sessions generated novel insight and understanding that wouldn’t have been possible through other methods. A key insight was the impact food insecurity had on food safety and food related behaviours. This was elicited from the discussion of the dependence on student loans for food, sourcing food through ‘bin-diving’, and the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on food security.

Key takeaways: What made these sessions so successful and how did we create an environment in which people felt comfortable discussing these sensitive issues?

- The nature of co-creation within a shared demographic group – a subgroup of the population that was in this case undergraduate students – meant the participants could relate to each other’s experiences and springboard ideas off each other.

- Following the lead of participants. A recurring theme of food insecurity arose within the co-creation sessions. The topic was handled sensitively, with questions asked in an open way and less probing questions to allow the participants to lead the conversations and feel comfortable.

- Conducting the sessions online supported access but took careful planning – hosting sessions online was not without challenges. The introductions and icebreakers at the beginning of the sessions were essential to making participants feel at ease with one another, build a rapport and replicate the face-to-face experience.

Engaging with students in an online survey revealed new insights for this underrepresented group.

The online survey was developed following the first few co-design sessions and was finalised in the final co-creation session with students. This was to ensure the questions and response options were clear and comprehensive.

A nationally representative sample of 2,921 undergraduate university students were recruited across England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland to take part in an online survey. Quotas were set based on Higher Education Statistics Agency data to ensure the sample was representative by gender, ethnicity, region and parental SEG.

The online survey touched on a wide range of food-related topics, such as knowledge, attitudes and behaviours surrounding food safety, food security and diet. As previously mentioned, some of the questions were taken and adapted from the FSA’s flagship consumer survey, F&Y2, so comparisons can be drawn between F&Y2 data and the student survey data. In depth demographic information was also included within the survey, so analysis could be drawn between the findings and demographic characteristics, such as year of undergraduate study, number of people in the household and parental socio-economic group (SEG).

Key takeaways: What did we learn through this survey about how to engage students and overcome ethical challenges?

- Recruiting students through a panel was an effective way to achieve a representative sample. Various recruitment tools can result in different demographic differences, however, the range of measures (e.g. quota sampling strategy and weighting) and sample size help to mitigate these effects.

- Using a specialist agency gave us access to a nationally representative sample of students that would not have otherwise been possible.

- Potentially sensitive questions were worded objectively to minimise the emotional impact and the survey anonymised. For example, closed rather than open questions, and language that remained factual rather than emotive.

- Utilising valuable data sources such as F&Y2 has been beneficial in terms of developing a high-quality survey and giving plenty of options for secondary analysis where robust comparisons can be drawn between students and the wider population.

Citizen Science engaged over 1,000 people with food safety dilemmas and allowed thousands of images to be coded – in days we achieved what would otherwise have taken months

The final stage of the research utilised the online citizen science platform Zooniverse. Citizen science is a mutually beneficial research approach, that actively involves citizens in the research and results in new knowledge and outcomes

We wanted to understand student food behaviour in more depth and detail. In our project, citizen scientists coded thousands of images of students’ fridges and sinks for good/bad food behaviour. This meant the scientist were also learning valuable lessons on food safety behaviours to incorporate into their own lives – win win!

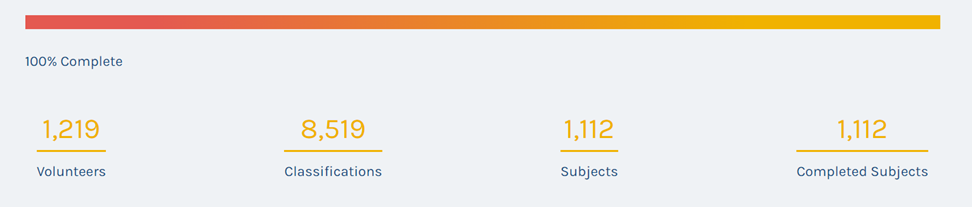

We settled on the ‘tempting’ title of ‘Grime Scene Investigation – Student Kitchens’ in the hope of drawing in as many volunteers as possible and we enticed 1,219 volunteers with 8,519 classifications! Who said food safety can’t be fun?!

The classification statistics taken from the project page on Zooniverse

What were the key benefits of getting citizen scientists on board?

- Analysing such a large data set without the support of citizen scientists would have taken an incomprehensible amount of time and resource.

- It is mutually beneficial, whilst citizen scientists generate meaningful data for us, citizens get to take part in a genuine scientific research project, and also further their knowledge of the rights and wrongs of food safety behaviours.

- Zooniverse is a very community-focused platform, so we have been able to collaborate with the citizen scientists on an individual level and generate valuable discussions around the topic of students shared kitchens.

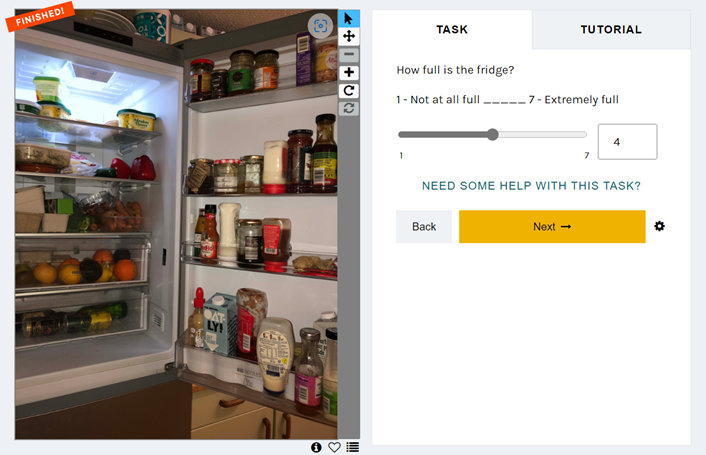

On the Zooniverse platform, we built the project under two ‘workflows’ – one for sink photos and one for fridge photos. Each workflow contained a handful of multiple-choice questions that related to the image; for example: ‘Which of these washing-up or cleaning items can you see? *Please select all that apply*’.

An example classification question on Zooniverse

Each photo was coded by 7 citizens, to validate the responses, before the photo was ‘retired’.

As a team, we were uncertain how long it would take for the images to be coded, but we were pleasantly surprised by the immense interest in the project – all the images had retired 1.5 weeks after we launched!

Key takeaways: What was the secret to our success and what should other people wanting to use Zooniverse keep in mind?

- Blurring/cropping the student images in preparation for uploading to Zooniverse was necessary to adhere to GDPR guidance and required a considerable time investment. This meant that a member of the student kitchens project team (myself) sifted through the thousands of images to spot those with identifiable information (such as name labels, university mugs and more!). Building in enough time to do this supported our delivery.

- Building the project on Zooniverse was straightforward due to the user-friendly design. However, it is important to give a lot of thought to clarifying question wording so citizen scientists know exactly what you want them to look for!

- Be sure to think of a creative title and description for the project. Our choice of ‘Grime Scene Investigation’ intrigued participants into clicking on ours!

- Staying engaged with the citizen scientists through the ‘talk boards’ feature. In particular for the weeks the project was live (but checking in after this period), it was useful to keep conversations going with participants – some needed clarity on classifications, others offering unique insights from their own experiences.

Next steps:

The next steps for the student kitchens project team are to conduct the analysis of the data from Zooniverse, of which there is a lot! This will triangulate the data from the co-creation sessions and survey to understand food safety behaviours. To do this, we will pair up the Zooniverse data with the survey data to get an in-depth picture of real-life student behaviours and how this correlates with students’ personal perceptions of food safety behaviours.

We have a thorough communications plan in place to disseminate the findings of the research and offer student specific guidance. The current student guidance that the FSA has provided is a useful starting point for this research to build upon.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank all of the citizen scientists who took part in this research, the co-creation participants, and student survey respondents.

Also, with thanks to Food Standards Scotland who partnered with the FSA for this research.