What’s changed for our qualitative projects

We recently completed fieldwork for the final wave of a longitudinal qualitative study for a Government department about refugees’ experiences of life in the UK. We interviewed refugee participants in different parts of the UK once a year over 3 years about a range of issues such as education, employment, learning English and where they live.

We conducted interviews with participants in their first language, including Arabic, Dari, Kurdish and Tigrinya. In previous waves we did these interviews in person with an interpreter present, but this year we conducted the interview via a three-way conference call between the participant, interviewer and interpreter.

We’ve also been conducting a multi-country qualitative project since late last year, which has used online focus groups as the main methodological tool. The project is being conducted for a leading academic institute, who are carrying out a wider study exploring trust in governance both nationally and globally.

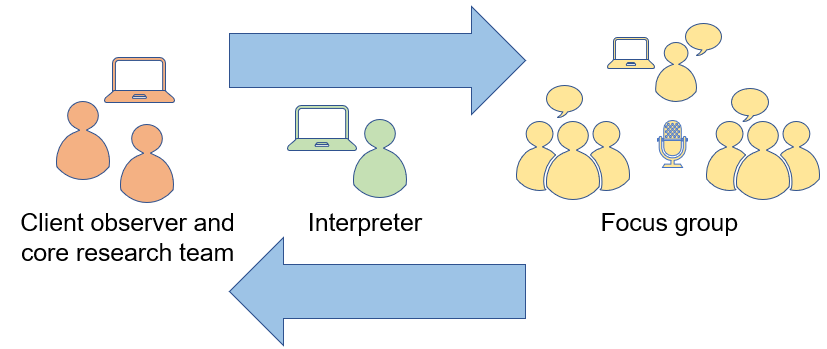

Given fieldwork took place across several countries where English was not the native language it was necessary to use interpreters. The interpreter’s role was twofold: they translated the discussion between participants and the moderator for the client and core team members (all based in the UK), and passed comments and instructions to the moderator from the observers throughout the group.

What worked well for interpreter-assisted qualitative fieldwork during the pandemic

Depth interviewing via Telephone Conference Calls

Three-way conference calls with an interpreter, moderator and participant worked well because most of our participants were already familiar with the research process where they had taken part in previous waves of the study. This meant we could schedule the first telephone interviews with these participants and test out the new approach. We were then confident in how the new approach worked in practice before conducting interviews with participants who were new to the study. We felt this was important because the longitudinal participants had a working relationship with our researchers and were receptive to us trying out the new approach before we used it with participants less familiar with the study overall.

This approach required a different way of briefing interpreters. Previously, we sent interpreters documents such as discussion guides and background information before the fieldwork period and held a face-to-face briefing session on the day of the fieldwork to confirm details and answer questions. Since moving to remote fieldwork, we have held briefing sessions over the phone days in advance of the fieldwork period. This means the research team can give themselves more time to answer questions from the interpreters, solve any unanticipated issues and make improvements to the interview process in good time before the first interviews.

Online Focus Groups

We undertook a similar transition in how we arranged briefings for online focus groups. We briefed our interpreters and moderators jointly for each country, with each briefing delivered by the UK based core project team and the client. By connecting our client to the interpreters at this stage, we found that it increased our interpreter’s engagement with the research. We discovered that learning about the study’s objectives first-hand from the client and having the opportunity to ask the client questions about the research made them feel connected to the research team and invested in the research process.

The interpreters’ enthusiasm led them to share additional notes with the core research team which explained colloquialisms and culturally significant events referenced by participants. In this secondary role, the interpreters acted as a bridge between the moderator who, as a native speaker, may not realise these things are unclear to others, and the core research team who may not be aware of these details. These insights from the interpreters proved to be invaluable for future analysis.

During the groups it proved helpful to have an external means of communication in real time between the observers and moderator via the interpreter. Using WhatsApp, clients texted their comments and requests to a member of the core team, who sent them to the interpreter, to relay to the moderator. This required interpreters to be adaptable to the needs of the observers and efficient in their delivery to the moderator.

A thorough understanding of Zoom, the platform we used to host sessions was also crucial to successfully running the groups. Our core research team developed a written guide which detailed how to set up and conduct a meeting using an in-built language interpretation feature. We sent this guide to our country teams and the research team conducted a technical briefing with them, including a test run of the language interpretation function with the interpreter, moderator and a technical assistant. By ensuring the team were confident using these features, we further minimised the risk of running into technical issues during the groups.

What we’ve learned for next time

While the move to remote interpreter-assisted interviews had benefits for fieldwork management, it nonetheless presented challenges in conducting the fieldwork itself. It was a challenge for us to gauge participants’ understanding of our questions without the benefit of non-verbal cues such as facial expressions and body language. When participants and interpreters were conferring over the meaning of a specific question, it was difficult for us as moderators to confirm that the participant fully understood without seeing their reactions. We were reliant on the interpreter to confirm if the participant understood or if they needed further clarification.

We addressed this challenge during the fieldwork period by emphasising that interpreters must translate questions verbatim and take sufficient time to clarify questions for participants, as needed. This experience highlighted the value of briefing interpreters in two or more shorter sessions that focus on specific aspects of the brief, such as content of the interview and the practicalities of telephone interviews. Structuring the briefing sessions this way made it easier for interpreters to take on the details of each aspect of the brief. This reduced the risk that interpreters might miss specific details, such as the importance of verbatim translation.

Our experience of running interpreter-assisted online groups showed that anticipating potential technological challenges was key to their success. Zoom has a language interpretation feature that worked for our purposes, but the two-channel function can prove to be challenging for those who are not tech savvy. Consequently, we now ask all participants to log into the discussion fifteen minutes before our scheduled start and have a technical assistant on hand to help participants with setting up.

As we’ve delivered more focus groups using this approach, we’ve found alternative methods of providing simultaneous interpretation. Another good option is to conduct the discussion on one online platform, such as Zoom (which the interpreter listens to) and provide translation via a second platform, such as Microsoft Teams. Thus, observers can watch the discussion through one platform, and listen to the interpreter’s translation via a separate one. This is a particularly good option if you require isolated audio of the group discussion without the interpreter’s translation mixed in.

Considerations for the future and long term benefits:

The transition to remote interpreter-assisted fieldwork allowed us to adapt ongoing projects to ensure we delivered them in a year of great change, as well as design projects we would have previously not thought possible. Looking to the future, remote interpreter-assisted fieldwork will be crucial for engaging people in innovative ways as well as meeting participants’ growing expectations that they can take part in research encounters online from their own homes. While there will continue to be a need to conduct fieldwork requiring interpreter support face-to-face, our experience of carrying out fieldwork this year has shown we can offer options to do this online or over the phone as well, improving the overall inclusiveness of research approaches and methods.

AUTHOR BIOS: Andrew McKeown and Zara Regan are both Qualitative Researchers in the new Qualitative Research and Engagement Centre at Ipsos Mori. Andy has been conducting qualitative research for five years using methods such as depth interviews, focus groups, and more recently, online ethnography, online communities and online deliberative events. Zara has over four years’ experience conducting qualitative research using a range of qualitative approaches including group discussions, depth and cognitive interviews, workshops, and ethnography, both in the UK and internationally.

Ipsos MORI recently announced the launch of the new Qualitative Research and Engagement Centre. The centre utilises a mix of traditional qualitative approaches, such as depth interviews, focus groups, workshops, ethnography, with cutting-edge Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality technologies to bring scenarios to life. It has expertise in a suite of democratic participatory methods conducted with a diverse range of participants, such as Citizens’ Assemblies, citizens’ juries, public dialogues and deliberative workshops.