In recent years there has been increasing interest in achieving impact from research. That has led to a focus on communicating research findings clearly, in accessible language and drawing out any implications for action. The psychology of how people receive and interpret our messages has been much less considered, however a growing movement has been rectifying this. The results are fascinating, and challenging.

At the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), we have been trying to use evidence to inspire changes in social policy for many years. Our goal is to create a prosperous UK without poverty, and we have always believed that robust evidence is at the heart of achieving this. For many years we also believed that if we gathered the best evidence and communicated it clearly enough to the right people, it would prompt the changes in policy and practice that the evidence suggested were necessary. That view has also commonly been held by researchers, campaigners and activists working on health, education, climate change, poverty, child development and many more. But it missed a vital part of the puzzle – what happens in people’s minds before, during and after we communicate our evidence.

Four years ago, we began working with the Frameworks Institute to develop a new way of talking about poverty in the UK. Our partnership was born out of a realisation that even our best communications did not seem to ‘land’ the messages we expected. We might present evidence showing that child poverty was rising and that cuts to social security were a major factor driving this. We would back this up with evidence of the damage that growing up in poverty causes to children’s development and prospects and the cost of that damage to the UK’s economy. To accompany robust quantitative evidence, we would bring in qualitative research demonstrating how poverty affected relationships, day to day lives and how this felt to the people involved. We might think we had presented a water-tight case for better support for families, only to find that the messages taken away were that people needed to learn to budget better and that cuts to benefits were necessarily to prompt more parents to work.

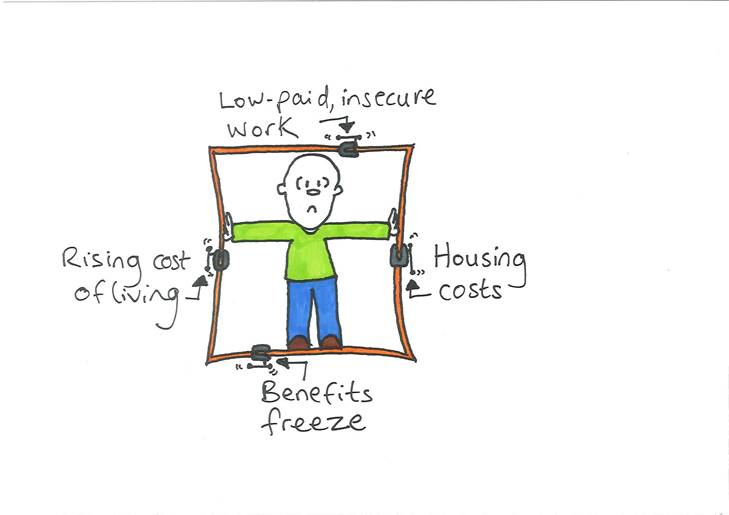

The approach taken by the Frameworks Institute started by investigating how people in the UK think about poverty: the mental landscape held in people’s minds before we even start speaking. Carrying out research with 20 000 people, the team identified nine cultural models – ways of defining poverty and understanding what causes it. Every person holds multiple, conflicting models in their minds. The way they understand any communication on the subject is shaped by which of these models is activated. This means that there is no ‘neutral’ way to present research findings. As soon as we begin to communicate, at least one of the models will activate.

For example, saying ‘People on low incomes are faced with impossible choices, between heating and eating’ risks activating the ‘self-makingness’ belief. This means thinking that someone’s situation is solely or mostly result of their choices or motivations. Once that belief is triggered it leads to thinking that the solutions are for people to try harder or make better choices. The role of context in shaping people’s lives is lost.

Once a cultural model is activated, everything that someone sees or hears will be interpreted through the prism of that set of beliefs. This explains why ‘myth busting’ doesn’t work. Repeating the myth activates that cultural model. Any explanation that follows, showing how the evidence shows the myth is incorrect, is interpreted through that cultural model. Facts that don’t fit are ignored, discounted or reimagined to fit the underlying beliefs.

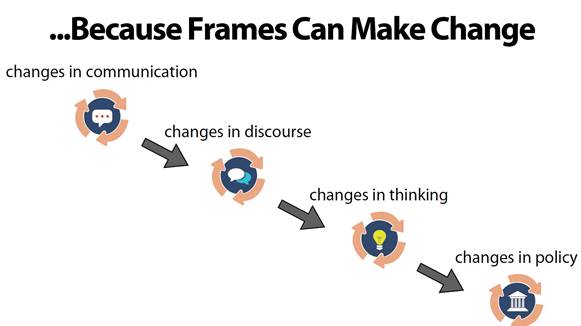

That’s the bad news. The good news is that there are also cultural models which are more in tune with the evidence, and which facilitate support for evidence-based action to achieve social change. Working with Frameworks, we developed new ways of talking about poverty and communicating our evidence. We now strive to ‘frame’ all our communications - from press releases to tweets, infographics, presentations, blogs and even informal conversations with stakeholders, friends and family.

That sounds like hard work. And at first it is. Communicating differently feels unnatural, it takes extra time and attention. But it quickly gained momentum because it worked. When I started to use the framing insights in speaking to the media, writing a blog or presenting to a stakeholder group, I could immediately see the difference. Conversations which had previously been frustrating, suddenly became much more constructive. The ‘take-away’ messages that we saw played back by the media, politicians and others tended to be the parts that were ‘framed’. Once again, we experienced the power of basing our actions on robust evidence rather than our own assumptions of what would work.

We have published a toolkit to enable other organisations and individuals to understand and use the insights we’ve gained through our work with Frameworks. The research report is published on the Frameworks Institute website, here, with a summary on the JRF website, here.

AUTHOR: Helen Barnard, Deputy Director of Policy and Partnerships, Joseph Rowntree Foundation - @Helen_Barnard