Whenever you tell someone you work in Behavioural Science, there’s often a reasonable assumption you have a psychology degree. After all the most well-known actors in our broader field are behavioural insights, the offspring of behavioural economics which was in turn born from economics and cognitive psychology.

And it does form the nucleus of what we do. The head of our team,

Carla Groom, is a doctor of psychology. Our key diagnostic tool,

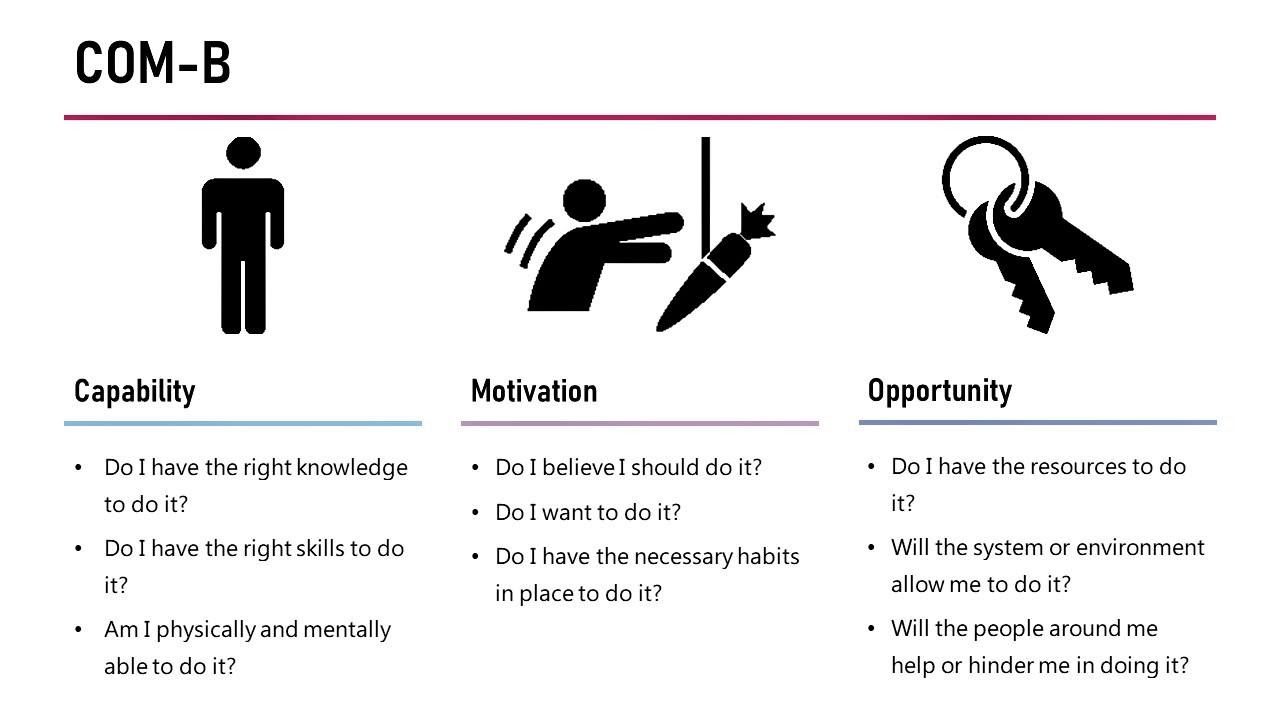

COM-B, is the product of a vast array of psychological research.

That might be why it surprises people that, as a Behavioural Science Advisor, my background isn’t in psychology. Likewise for a significant portion of our team. But it’s not the case that we function in spite of that – we thrive because of it.

Because for us, Behavioural Science isn’t a particular body of practice or knowledge. It’s a certain way of thinking. Human-centric thinking which looks at both the perspective of the people concerned and the systems they operate in and where context reigns supreme.

A key part of that is getting a deep, complete understanding of the problem before coming up with the solution. Our problem statement is straightforward: “Sometimes DWP makes decisions based on assumptions about behaviour that aren’t accurate”.

For example, when helping to deal with staff not following security protocols, we found an assumption that they weren’t doing so because they didn’t know how, or didn’t care enough. However, we found one area where people would diligently lock their documents away, and then hang those keys in the appropriate key cabinet. But there weren’t enough keys for that cabinet or clarity about who was responsible for locking and unlocking it. So rather than just focusing on people’s knowledge or attitude, we needed to look at the environment too.

In turn, we look to what we need to find the true sources of the problem and find the reality of behaviour. Where the tools to do that come from doesn’t matter - just that they work. Which is why when you look at our backgrounds, and all our tools and methods, they come from cognitive and social psychology, but also anthropology, economics, user design and research, linguistics, social research, philosophy, and evaluation methodology.

Those tools, and those ways of thinking, are embedded into each of the 4 stages of how we approach any given problem.

0. Start Upstream

This isn’t part of the process itself but it’s a very important pre-script. We always want to look at the wider problem. Traditionally the application of behavioural insights or “nudge theory” happens quite late in the day. It takes a well-defined problem and looks to find a low-cost intervention to help tackle it, or tweak an existing solution to optimise it. These are important, but bringing in behavioural thinking late also has its limits. An intervention is only as good as the diagnosis, and behavioural thinking has just as much to offer about why problems happen in the first place.

It also means you’re only looking at one or two interventions, but complex problems will normally need many. If you think of any great challenges, from climate change to regional development, there’s never one solution. There’s many things that have to be done together.

1. Refine Intent

It’s crucial to be clear as to what it is that people want to achieve. Are we asking enough “whys?” and getting to the root of the concern, or dealing with a proximate problem? Are we making sure we understand all of what our commissioner is trying to achieve, and the intent behind their problem statement? Rigorous clarity of purpose is called for, because it’s all too easy to not uncover assumptions (which is not to say mistakes) they might have about the problem, or to inadvertently add in our own.

To this end we want to vanquish ambiguity. Are we clear on what is meant and intended by various terms, particularly as it applies to the problem at hand? I have become somewhat notorious for my growing list of “potentially problematic” words which can sometimes hide many different meanings or be easy to use but hard to meaningfully define for a specific situation e.g.. “culture change”, “strategic” and “engagement”.

2. Define behaviours

With intent established, we then define the behaviours needed – what has to happen for the outcome to be realised? Two things here are key – establishing a bona fide behaviour (observable, explicit action – who’s doing what, when and how) and logical and evidential rigour. Will this behaviour achieve what we want it to? Stopping all cars with license plates ending in a certain digit driving into a city would seem a sure fire way to reduce air pollution, but is that necessarily the case?

3. Understand the barriers

Then we look at what the barriers to those behaviours are – why are people not already doing the behaviours in question. Our key tool for this is COM-B. Originally developed by the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London, it says people need 3 things - sufficient Capability, Opportunity and Motivation – for a given Behaviour to happen. And where a part of any of those three are missing, you have a barrier to your desired behaviour.

Then we look at what the barriers to those behaviours are – why are people not already doing the behaviours in question. Our key tool for this is COM-B. Originally developed by the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London, it says people need 3 things - sufficient Capability, Opportunity and Motivation – for a given Behaviour to happen. And where a part of any of those three are missing, you have a barrier to your desired behaviour.

In finding out what those barriers are, you need to start with empathy and let it lead you to curiosity and openness. For empathy, take the perspectives of the people involved – what’s easy, what’s difficult, and what makes it difficult? For curiosity, look at what explains their current behaviour, seek out context relevant, empirical evidence, and going where it leads you. User research methods (particularly when augmented with other tools from behavioural science) are invaluable here. For openness, COM-B is especially useful, because its role is to get you to look at all the possible barriers. Not just whether people sufficiently understand, or have the right attitude, but whether they’ve got supportive habits, or the right environment or the necessary resources.

4. Removing barriers

Finally comes removing those barriers. Two things are crucial here. The first is to carry over that empathy and openness by working with realistic assumptions about who people are and what motivates their behaviour, and design interventions based on that. When it comes to designing systems or processes, design it around people, rather than finding a “perfect” system/solution and then trying to change people to fit it.

The second is to always work collaboratively with colleagues in and outside of DWP to co-produce these solutions. We thrive because we view no discipline as having a monopoly on wisdom, and that is just as true between teams as it is within one. Even more so when it comes to implementation, behavioural thinking only has value when it can be translated into the real world.

In conclusion

As you can see from these steps, we have COM-B – a tool taken from psychology - but none of the steps require a degree in it. We’ve used psychology as a starting point but use whatever tools we think helps without regard for where they come from. We’re able to do that because form follows function, and we know that our value isn’t in being psychologists. Our value is the process and the way of thinking it exemplifies. We have found maximum value comes from holistic and deep understanding, usually embedded in individual perspectives and contexts, and engaged with as early as possible.

Further Reading

Three principles for better thinking about behaviour – Transforming Together blog on GOV.UK

Strategic communication: a behavioural approach – Government Communication Service

From micro to macro: establishing a strategic role for behavioural science – Best of behavioural science in UK government, BX 2019 Conference

Author Details: Nathan is a Behavioural Science Advisor at the Department of Work and Pensions’ Behavioural Science team, where he mainly works on health and disability benefits and communications. Prior to this he worked at the Cabinet Office for the Government Communication Service, where he co-authored “Strategic communication: a behavioural approach”.