What is Polis?

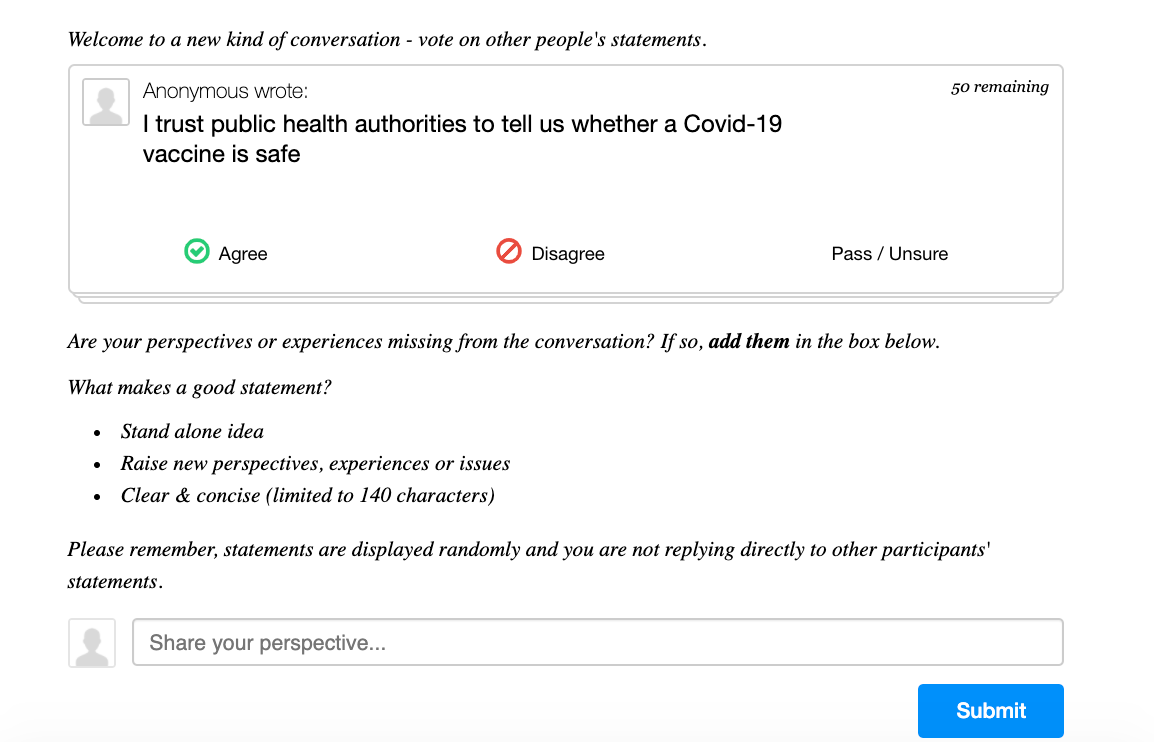

What separates Polis from a standard poll is its interactivity. It involves people in the conversation directly, by enabling them to contribute their own statements and ideas. So, what exactly does this tool involve? When accessing Polis, users are directed to something that looks like the following page:

A study progresses in this way:

Recruitment: The choice of participants is up to the researcher - samples can be open-access, a nationally representative sample, or include people from a specific group or organisation.

The researcher starts the conversation: Participants are presented with a series of statements, which they can either agree with, disagree with or pass on. This initial set of statements are provided by the researcher, to try and understand the range of views on a topic, as well as how different (and sometimes controversial) perspectives interact.

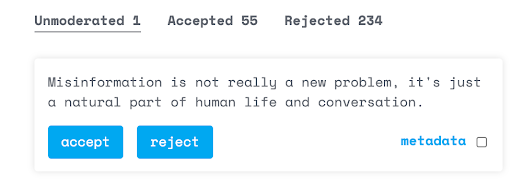

Participants submit comments: After they’ve worked through the statements pre-loaded by the researcher, participants can submit comments of their own. These are then presented within the Polis interface as ‘unmoderated’ comments. See one example (created by me) below:

Participants’ comments become questions: As these comments flood in, we moderate the submitted statements, rejecting unclear, off-topic, confusing or disrespectful comments. We also have to be somewhat selective with how many comments we accept, as participants are unlikely to vote on every statement if too many are included. This means that only the most insightful statements or those which reflect the views of many respondents are placed back into the pool of questions, to be voted on by other users. So, while the researcher directs the Polis by curating the statements - and must be careful to reflect participants’ views, rather than their own - it is users who really end up shaping the direction of the conversation.

Analysis - Grouping statements together: For example, we could find out that people who agree that: ‘We should trust the recommendations made by public health officials about Covid-19’ are also likely to disagree with the statement that ‘Fake news and misinformation makes people believe Covid-19 is more dangerous than it really is’. This helps us understand not only what people are thinking, but allows us to draw links between statements, to understand why they might be thinking it.

Analysis - Grouping people together: Polis also analyses participants’ responses, dividing them into different groups based upon the attitudes they share with other people who responded to these statements.

So to recap, in principle, this tool provides the researcher with four main advantages:

- The chance to start and direct a conversation on an interesting topic.

- The opportunity to gather public opinions and map how different views interact.

- The ability to empower the public to contribute their own statements.

- Intelligent mapping of groups which define the participants (see more on this later.)

Polis in Practice - My Work on Fake News and Misinformation

To explore what this process feels like as a researcher, I’m going to take you through a recent Polis I ran on fake news and misinformation for Demos.

We began by recruiting participants, which involved sharing a link to the online poll via our social media channels and mailing lists. Crucially, this meant the results were not nationally representative. This means that we’re more interested in mapping interactions between viewpoints, rather than looking at levels of support for particular statements (given that we couldn’t tell exactly how far our respondents reflected the population at large). This process has recruited 751 participants into the study so far, placing a total of 27,252 votes, and gave us a detailed look at their views on misinformation and fake news during Covid-19.

We also received over 288 comments from participants - ranging from policy recommendations (‘Social media businesses should be treated as publishers and so be liable for what they host’) to analysis (‘Fake news has become believable because people have lost faith in the reliability of official news media’) and a comment from one rather strong proponent of traditional newspaper coverage (‘Social media is a poor source for any news. I recommend that all households are regularly sent a paper copy of The Times newspaper to read’). These user-submitted comments bring the poll to life - and their inclusion in the poll helped us explore people’s views on themes which we had not planned to explore at the outset of the poll.

Generally, the quality of comments was incredibly high - people were recommending new ideas around content filtering, fact-checking and combating fake news which we had not expected. Carefully curating these statements to drive an interesting conversation was a vital part of this work. So we tried to feed in statements which provided a revealing perspective on misinformation, or came up with new ways to tackle fake news - and rejected those which added less insight into the topic.

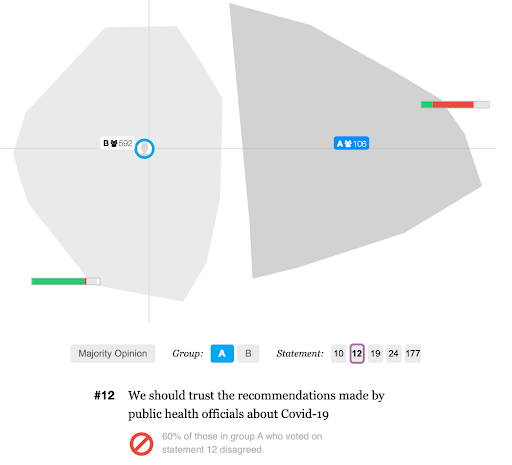

Ultimately, Polis then produced the following mapping of the participants who completed our research. These groups are formed by clustering people likely to vote similarly across various statements, and they show a stark split, between Group A (just 106 people) and Group B (592 people).

As well as showing us how participants are divided into groups, Polis allows us to explore their perspectives. In the example above, we can see that 60% of the smaller group would not ‘trust the recommendations made by public health officials about Covid-19’, whereas the vast majority of Group B would (the green bar).

In short, Polis showed us not only what people thought and what they wanted to say, but also helped us understand how we should interpret the results, through mapping these two opinion groups across the range of statements.

Achieving consensus through dialogue

Ultimately, tools like Polis are vital to help us understand what people think. They allow us to count and measure opinions, like a traditional survey, but also build a dialogue, to offer - in an online tool - a form of participation much closer to a focus group. In the age of Covid-19, tools like these are even more valuable, as they help us map what divides us and what brings us together in the public square. Polis is helping us advocate for policies which achieve consensus, rather than division.

The full results of our misinformation and fake news Polis will be published in our next Renew Normal report later this year. For now, you can try out Polis for yourself, via our recent surveys on topics ranging from key workers, to online life, communities and volunteering. Just visit:

https://renewnormal.co.uk/latest-surveys/.

AUTHOR BIO:

James Sweetland is a Research Trainee at Demos, Britain’s leading cross-party, independent think tank.